(Follow up to the Resilience blog)

Blog post by Eric Moya Cst-D, Ms/Mfct

A lot of people are really stressed out.

That might be one of the most obvious ways to begin a blog entry possible. Seriously, I don’t imagine that I would have too difficult of a time (in conversation or in front of a classroom) trying to make the argument that there are a lot of people in the world experiencing fairly high levels of stress, anxiety, worry. And research bears this out. Some stress related statistics in the US reveal that 1 out of 3 people describe themselves as living with “extreme stress”. Flesh these statistics out[i] and you begin to realize the immense problem that sustained stress can be upon us. The cost is high - to employers, individuals, families and general wellbeing.

Since it is a topic I discuss frequently, it’s a fairly regular occurrence for people to come up to me and ask me what I mean by “depletion” or “chronic depletion”. It seems to be a term that many people identify with. Even more, it seems to be an idea for which people want answers, both for themselves as well as for friends and family. Basically, informal research would suggest that almost everyone has some connection to the topic of depletion and chronic depletion.

The idea of depletion, for me, at least is closely related to the concept of resilience. And let me encourage the reader to go read the blog titled, “resilience” before reading this blog, if you haven’t already. Depletion is basically the flipside of resilience. Let’s explain that further . . .

Stressors

The concepts of “stresses” and “stressors” are pretty intuitive to many of us. Even if we haven’t bothered to look up a formal definition, we know on a bodymindsprit level when we have stress as well as the types of things that tend to cause us stress (i.e-stressors).

Personal experience is that most people have a negative view of stress, generally having the belief that life would simply be much better if we did not have stresses or stressors. I don’t actually agree with this. Without stress, we wouldn’t change, transform, or evolve. It is important to remember that the discomfort of a healthy amount of stress also gives us the energy and the motivation to make change in our lives.

It is a healthy stress that benefits by giving us the impetus for things to be different. It is the motive for change, growth, and evolution. So, to that end, it is helpful to take a bit more generous of a view on stressors and recognizing that they may not feel pleasant, but they also help us to grow and evolve.

The more formal definitions of the words “stress” and “stressor” are as follows:

- A “stressor” is just something that creates “stress” on an organism.

- “Stress” on an organism is when “changes in the external or internal environment are interpreted by an organism as a threat to its homeostasis”. [ii]

The main point being that stress is a perceived threat to which our organism has to respond. As long as our organism is able to respond, then we do okay, and the movement to remove the stressor helps us. We can apply this on the body, mind, and spirit level.

Of course, not all stressors are going to be equal. For example, it doesn’t make sense to place a 5K run and a deadly poison in the same category of “stressor”. A deadly poison may be a stressor, but its not going to propel someone to greater health. Likewise, alcohol might be a stressor on the body, but if it is being used to mask or avoid uncomfortable feelings, then there is little change towards health.

So, although not all stressors are equal, the main point to be made in this article is that stress isn’t inherently a bad thing. We need some amount of healthy stress to propel us forward, to help us grow and develop. And like a lot of things, too much can be a bad thing . . .

Depletion/resilience

Imagine for a moment that you could list all the stressors you currently have in your life, body, mind, and spirit. That list would include all the stressors you consciously know about. It would also include all those factors in your life which provide stress for which you may not consciously know about. Now imagine that you could then chart that number on a graph as it fluctuates in your life. If you have relatively few stressors, then it will take its toll on your bodymindspirit, but it will be a relatively slow toll. If you have a LOT of stressors, then it will take its toll on you more quickly and severely. At the same time, also imagine that it were somehow possible to chart the sum total of your body’s ability to compensate for those stressors.

Your “capacity for compensation” includes EVERYTHING your bodymindspirit can do to restore its homeostasis. For example, your body can heat itself up when it’s cold. It can cool itself down when it is hot. It can clean your blood and remove wastes. It can heal itself when it is injured and mount immune responses when you are sick. Psychologically, you mind can strategize and learn and avoid discomfort. You can create stories and self-talk to understand things you may not initially understand about yourself and the world. And spiritually, you work to find meaning and purpose and connection and to wrestle with concepts of death and life. Threats to that also require adjustments and compensation.

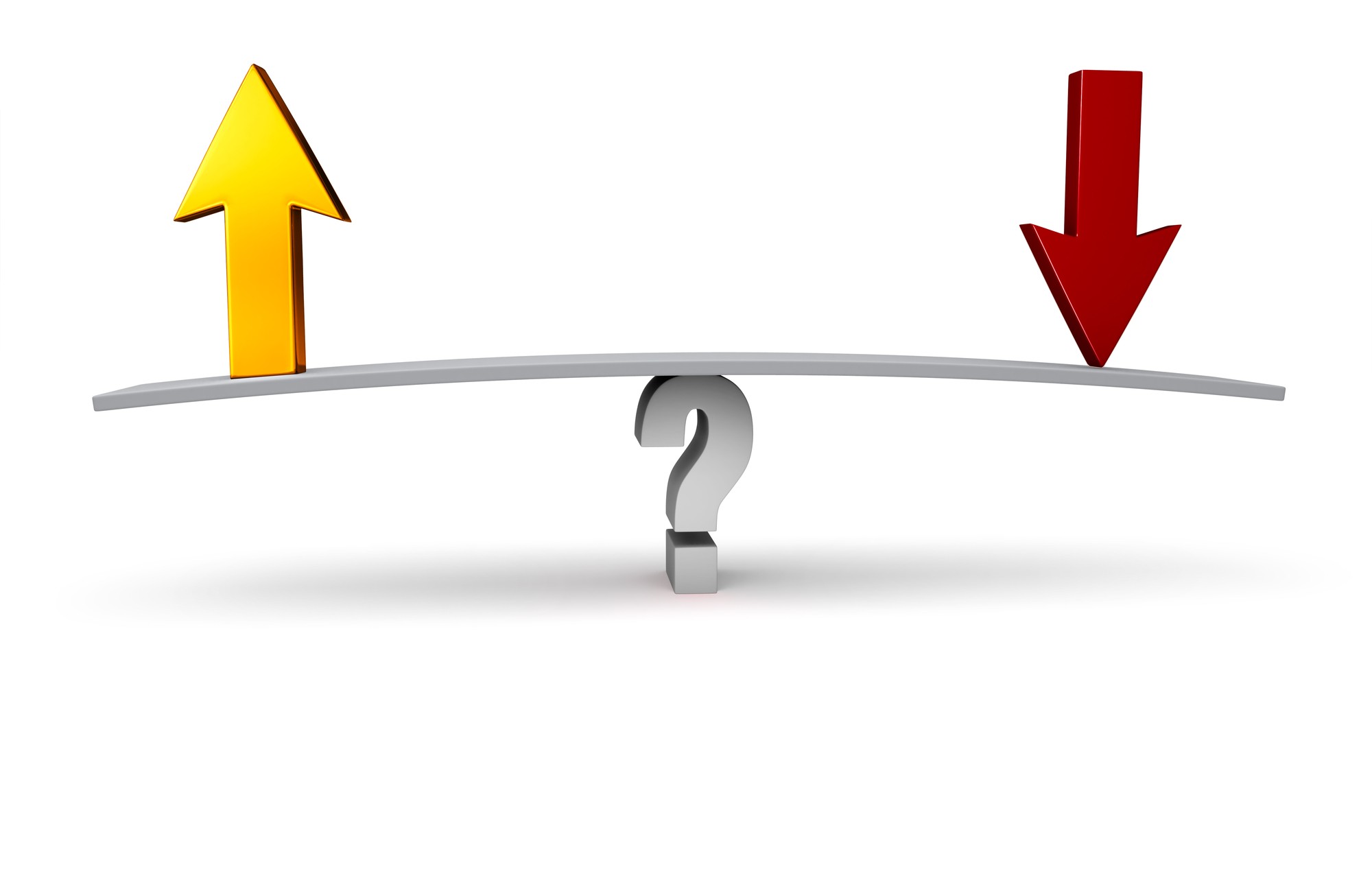

So, imagine you have the sum total of your stressors and you also have the sum total of your capacity to compensate. If your stressors are greater than your capacity to compensate, you are depleting yourself. You could say that you are losing ground, so to speak. And if your capacity to compensate is greater than your stressors, then you are building resilience.

Chronic depletion compared to a healthy life

Once upon a time, I would have argued that we want to spend our lives in resilience, that we should work to always have our capacity for compensation be greater than our stressors. After years of working with people therapeutically, I don’t believe that to be the case any more. After watching people grow and develop through various challenges and life stages, I’ve come to believe that in a healthy life, we naturally oscillate back and forth between depletion states and resilience states. When people are feeling good and full of energy, they naturally begin taking on more life tasks and new challenges. Examples of taking on more challenges might include starting a family, going back to school, beginning a new exercise routine, moving to a new location, etc. And when a conscious self-aware person begins to feel overly stressed, he or she will naturally move to remove stressors.

In a lot of ways, you might even imagine the dance back and forth between depletion states and resilience states to be a form of bodymindspirit biorhythm – primitive energies which help propel us through lifestages and individuation from childhood into adulthood and old age.

Chronic depletion, however, is what happens when someone is unable to right that balance and spends too long in a depleted state. Perhaps the stressors are too great, or the person is too devitalized, or the stressors are too pervasive or unchangeable within that person’s life. Someone with a chronic illness, in constant pain, without social support, and from a disadvantaged society group has bigger hurdles for changing that resilience/depletion state than someone with good health, a good support network of friends/family, ample financial resources, and from a culturally dominant social group.

As demonstrated in that last example, the contributing factors of stressors can become significantly complex. We have our genetics, our health, our lifestyle, our social environment, our psychology, and our spiritual life all playing into our ability to remove stressors. The longer someone spends in a depleted state, the more likely they will move into “chronic depletion”.

Chronic depletion and depletion “vortex”

There is a very interesting thing that seems to happen when people spend too much time in a depleted state. As stressors deplete someone, each new stressor seems to have a bigger impact, and the bigger the impact the greater the depletion. By the time someone is in a state of “chronic depletion” it means that he or she has almost zero capacity for compensation and each new stressor which occurs is going to upset the system way more profoundly than that particular stressor should. This is what I would call a depletion “vortex” or a state of chronic depletion.

I remember a client I had about 17 years ago. Her condition at that time was described as “General Adaptation Syndrome” which is a term used for extreme stressors placed upon the body and its predictable reactions to them. I would ask her what her experience of her own body and condition was like and she would describe to me sitting on her couch at home and being unable to summon enough energy to get up and attend to the activities of life. She would describe the phone ringing and bursting into tears. Imagine that experience for a moment. For all of us, the phone ringing is a mild stressor and it propels us to either get up and to answer the phone or turn off the ringer. But imagine being so physically and mentally exhausted that just the phone ringing causes a state of overwhelm to your system from which it takes a long time to recover. This would be what happens when a person loses their capacity to compensate for new stressors.

Sadly, once a person becomes chronically depleted, it is usually going to be a long and challenging road to recover from it. It becomes a process that involves a complex mixture of lifestyle change, effective manual therapy, effective psychological therapy, and acquiring new behavior patterns. The good news is that is very possible to recover from chronic depletion, but it is a marathon and not a sprint for both the therapist and the client. As I emphasize to practitioners in the classes I teach, the best work we might do as practitioners is to help people prevent themselves from becoming chronically depleted.

In a future blog, I think I’ll plan on talking a bit more about some of the clinical implications and presentations of chronic depletion, but for now, this introduction should begin helping us understand that true depletion is a bodymindspirit phenomenon beyond any one particular body system or mental state.

[i] S. (2017, May 18). Stress Statistics. Retrieved August 16, 2017, from http://www.statisticbrain.com/stress-statistics/

[ii] Badyaev, A. V. (2005). Role of stress in evolution: From individual adaptability to evolutionary adaptation. In Variation (pp. 277-302). Elsevier Inc.. DOI: 10.1016/B978-012088777-4/50015-6